From Fatty Liver to Cancer: A Guide to Key Signs

Why This Journey Matters: Orientation and Outline

Many liver problems move quietly, like a tide creeping in at night. Fatty liver is often the first wave—common, subtle, and surprisingly reversible—but in a fraction of people it rolls forward to inflammation, scarring, cirrhosis, and in some cases liver cancer. Worldwide, fatty liver affects roughly one in four adults, paralleling trends in weight gain, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes. Most people have no pain and feel fine, which is exactly why knowing the key signs—and what to do about them—matters. Think of this guide as a map with clear landmarks, so you can recognize where you are and how to steer toward safer water.

Here is the outline you’ll follow, with each part expanded in depth below:

– The early station: fatty change and the first lab or imaging clues

– The middle stretch: fibrosis and how to spot scarring before complications arrive

– The tipping point: cirrhosis, what “compensated” versus “decompensated” means, and why it changes everything

– The red-flag zone: signs that suggest cancer and how clinicians evaluate risk

– The action plan: prevention, surveillance, and practical steps you can start now

A few grounding facts to keep perspective:

– Not everyone with fatty liver progresses; many stabilize or improve with weight loss, activity, and metabolic control.

– Inflammation (often called steatohepatitis) raises long-term risk and can hasten scarring.

– Cirrhosis, even when silent at first, is the major risk state for liver cancer and needs routine surveillance.

– Early detection works: catching scarring or tumors sooner expands safe options and improves outcomes.

As you read, look for patterns rather than any single symptom. A lab trend plus a risk factor plus a new sign is more meaningful than one item alone. The goal is not to turn you into a specialist, but to give you the language and milestones to have a focused, timely conversation with your clinician. Small, steady choices—tracked with sensible tests—often change the story.

From Fatty Liver to Fibrosis: The Early Signals You Can Catch

Fatty liver begins when excess fat accumulates inside liver cells. Early on, it usually causes no pain. Many people learn about it after an ultrasound mentions “steatosis” or when routine labs show mild elevations in ALT and AST. While one abnormal test can be a fluke, patterns matter: ALT often rises first; as scarring progresses, AST may catch up or surpass ALT. Platelet counts can drift downward with advancing fibrosis, and alkaline phosphatase or bilirubin may tilt upward later. These shifts evolve slowly, which is why periodic checks, rather than one-off tests, are useful.

Noninvasive tools help separate low from higher risk. A widely used index, FIB-4, combines age, AST, ALT, and platelets to estimate the chance of advanced scarring. Practical thresholds used in clinics:

– FIB-4 below about 1.3 suggests low risk in many adults

– FIB-4 above about 2.67 points to higher risk that warrants specialist input

– Values in between are a gray zone requiring context and, often, further testing

Imaging contributes more pieces. Ultrasound confirms fat but cannot quantify scarring well. Elastography (a type of ultrasound that estimates stiffness) offers numerical clues:

– Stiffness roughly above 8 kPa may indicate significant fibrosis

– Stiffness above 12–14 kPa often raises concern for cirrhosis, depending on the device and setting

Risk is not one-size-fits-all. Factors that increase the chance of moving from fat to inflammation and scarring include central obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, high triglycerides, hypertension, older age, and certain genetic variants. Sleep apnea and hypothyroidism can also contribute. Practical early signals you can watch for:

– Unexplained fatigue or reduced exercise tolerance

– Mild, persistent right-upper-abdomen fullness rather than sharp pain

– Gradual, recurrent increases in ALT or AST on routine panels

– An ultrasound report noting moderate to severe steatosis

What to do with these signals? Discuss a structured plan with your clinician: repeat labs in three to six months; calculate FIB-4 using current values; consider elastography if FIB-4 is high or indeterminate; address metabolic drivers with nutrition, activity, sleep, and glucose control. Importantly, set a destination: a realistic weight-loss target (often 7–10% of body weight over time) is associated with lower liver fat and improvement in inflammation in many people. Early actions tend to pay compounding dividends.

Crossing into Cirrhosis: Complications and Clinical Clues

Cirrhosis is extensive scarring that remodels the liver’s architecture. Early (compensated) cirrhosis can be quiet; liver function remains adequate, and people may feel normal. Over time, pressure builds in the portal vein, and liver performance wanes. Recognizing this transition matters because it raises the risk for serious events and changes how clinicians screen for cancer.

Clues that cirrhosis may be present include:

– Platelets trending low, sometimes under 150,000, from splenic sequestration

– A firm or nodular liver edge on exam, and an enlarged spleen on imaging

– Elastography stiffness often in the 12–14 kPa or higher range (device- and context-dependent)

– Ultrasound showing a coarse, nodular liver with signs of portal hypertension (e.g., enlarged spleen, collateral vessels)

As the condition decompensates, warning signs appear:

– Ascites: new abdominal swelling from fluid accumulation

– Jaundice: yellowing of the eyes or skin, often with dark urine and pale stools

– Variceal bleeding: black, tarry stools or vomiting blood, requiring urgent care

– Encephalopathy: confusion, sleep–wake reversal, or slowed thinking due to toxin buildup

Basic lab patterns that signal worsening reserve include rising bilirubin, prolonged INR, and falling albumin. Clinicians often track composite scores that predict risk and guide timing for transplant evaluation. Even without formulas, the practical message is clear: new fluid in the belly, bleeding, confusion, or progressive jaundice are urgent red flags.

What can you do earlier to avoid reaching this cliff? Several steps have outsized impact:

– Keep vaccinations for hepatitis A and B up to date if you are not immune

– Limit or avoid alcohol, especially when any scarring is suspected

– Tackle metabolic drivers with sustained, achievable habits rather than quick fixes

– Ask about endoscopy to look for varices if cirrhosis is confirmed

Finally, surveillance begins here. People with cirrhosis generally benefit from imaging of the liver every six months to detect small lesions when they are more manageable. This cadence can feel relentless, yet it shifts the odds in your favor by bringing issues to light when options are broader and safer.

When and How Cancer Enters the Picture: Key Signs and Diagnostic Paths

Liver cancer most commonly arises as hepatocellular carcinoma in the setting of cirrhosis. The yearly risk in cirrhosis varies but often sits in the low single-digit percentage range, high enough to justify surveillance because early-stage tumors can be treated more effectively. Notably, liver cancer can occur without cirrhosis in fatty liver disease, particularly in older adults with diabetes, although the absolute risk is lower. Understanding signals—subtle and bold—helps separate everyday noise from signs worth swift evaluation.

Symptoms that raise concern include:

– Unintentional weight loss or loss of appetite over weeks

– Persistent right-upper-abdomen pain or a sense of fullness not explained by meals

– New or worsening jaundice, itching, or dark urine

– Rapidly increasing abdominal girth, sometimes with ankle swelling

– Sudden, unexplained derailment of glucose control in someone previously stable

Laboratory markers can support suspicion but rarely clinch the diagnosis alone. Alpha-fetoprotein may rise with certain tumors, yet many small cancers have normal levels, and benign conditions can also elevate it. Imaging leads the way. On contrast-enhanced studies, characteristic patterns—arterial phase “lighting up” followed by washout—point strongly to hepatocellular carcinoma. In a surveillance context, even small nodules trigger a defined sequence of follow-up imaging at short intervals to distinguish benign from malignant growths.

Who should be in surveillance programs?

– Almost everyone with cirrhosis, regardless of cause, unless overall health makes treatment unlikely

– Select high-risk individuals without cirrhosis, such as older adults with fatty liver and multiple metabolic risks, after discussing trade-offs

– People with prior liver cancer treated successfully, to catch recurrences early

The cadence is purposeful: ultrasound every six months is common, sometimes paired with blood tests. If a study is technically limited—common in obesity—clinicians may consider alternatives to improve visualization. The guiding principle is simple: regular, good-quality imaging plus timely escalation when something new or atypical appears. This rhythm catches more cancers when they are small, which can open doors to curative or liver-sparing options that would otherwise close.

Putting It All Together: Prevention, Monitoring, and a Pragmatic Plan

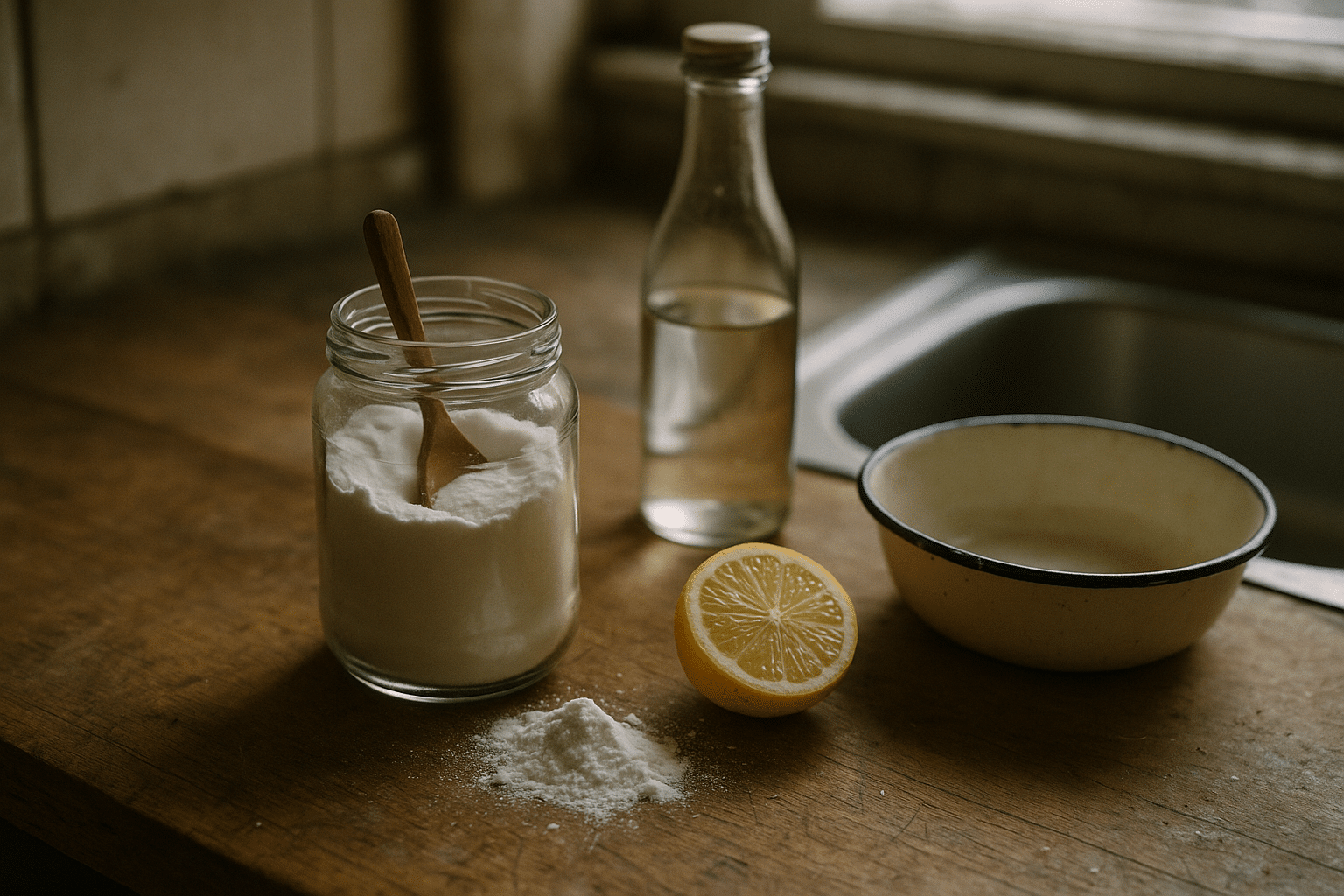

Prevention and early action do not rely on perfection; they depend on consistent, modest steps. Weight loss of about 7–10% is often associated with improved steatosis, reduced inflammation, and, in some cases, regression of scarring. A nutrient-dense, Mediterranean-style pattern—vegetables, legumes, whole grains, fish, nuts, olive oil—supports weight goals and metabolic health. Limiting added sugars and refined starches reduces liver fat. Physical activity matters even independent of weight change: aim for 150–300 minutes per week of moderate aerobic exercise plus two sessions of resistance training, scaled to your abilities.

Additional lifestyle levers:

– Prioritize sleep; treat sleep apnea if present, as nocturnal hypoxia worsens liver stress

– Avoid heavy alcohol; if any scarring is suspected, abstinence is the safer path

– Coffee, in moderate amounts, has been associated with lower liver-related risks in observational studies

– Manage cholesterol, blood pressure, and glucose, since each piece lightens the liver’s load

Medical therapy is individualized. In people with diabetes or marked insulin resistance, medications that improve metabolic health can reduce liver fat and inflammation, though responses vary. Vitamin E may be discussed in non-diabetic individuals with biopsy-proven steatohepatitis, balancing benefits and risks. None of these are quick fixes, and they work best alongside sustained nutrition and activity changes.

Build a monitoring schedule that is easy to follow:

– Repeat liver panel and platelets every 3–6 months while you adjust habits

– Track FIB-4 twice a year; consider elastography if values are high or drifting up

– If cirrhosis is confirmed, schedule liver imaging every six months, and discuss endoscopy for varices

– Keep vaccinations current and review medications and supplements for liver safety

Conclusion: A smart, steady plan turns concern into action. Notice patterns early, pair them with risk factors, and escalate evaluation when clues line up. Small, repeatable choices—an extra twenty-minute walk, a swap from sugary drinks to water, a regular bedtime—are surprisingly powerful when done week after week. With clear thresholds, consistent monitoring, and timely conversations with your clinician, you can change the trajectory from uncertainty toward control, keeping the tide in your favor.