A Comprehensive Guide to Esophageal Cancer

Introduction

Esophageal cancer matters because it often develops quietly, and when it speaks up, it does so with symptoms that can be easily dismissed until the disease is more advanced. Understanding how the esophagus works, which risk factors are modifiable, and what modern diagnosis and treatment involve can change the course of a conversation in a clinic—and sometimes the course of a life. This guide blends clinical insight with practical advice to help readers navigate a complex topic with confidence and compassion.

Article Outline

– Understanding Esophageal Cancer: Anatomy, Types, and Global Burden

– Risk Factors and Prevention: From Lifestyle to Environmental Exposures

– Signs, Symptoms, and Diagnosis: From Subtle Hints to Definitive Tests

– Staging and Treatment Options: Surgery, Systemic Therapy, and Radiation

– Living With and Beyond Esophageal Cancer: Nutrition, Side Effects, and Supportive Care

Understanding Esophageal Cancer: Anatomy, Types, and Global Burden

The esophagus is a muscular tube, about the length of a forearm, that guides food and liquid from mouth to stomach through a coordinated series of squeezes. Its lining is not uniform: the upper and middle segments are covered by squamous cells, while the lower segment near the stomach transitions to gland-forming cells. This anatomical landscape sets the stage for the two principal types of esophageal cancer: squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. The former tends to arise in the upper and middle esophagus, while the latter more often starts in the lower esophagus, especially where chronic reflux has changed the lining over time.

Squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma share the same neighborhood but have distinct life stories. Squamous tumors are more strongly linked to tobacco and alcohol exposure, and they remain more common in certain regions of Asia and Africa. Adenocarcinoma has become more frequent in many Western countries, paralleling increases in chronic acid reflux and obesity. A long-standing complication of reflux, called Barrett’s esophagus, reflects a cellular adaptation that can raise the risk of adenocarcinoma; not all Barrett’s changes progress, but monitoring can catch early trouble.

Globally, esophageal cancer is a major cause of cancer-related mortality, ranking among the most lethal malignancies because it often presents late and because the esophagus sits close to critical structures such as the trachea, aorta, and nerves that control voice. Early tumors can be silent, or they may cause symptoms so subtle—like a preference for softer foods—that they pass unnoticed. When narrowing occurs, swallowing difficulty usually starts with solids and may advance to liquids, signaling a need for prompt evaluation. These cancers are more common with increasing age and occur more often in men than women, though anyone can be affected.

Thinking of the esophagus as a narrow tunnel helps explain the disease’s behavior. A small growth can significantly disrupt flow, and the confined space invites local spread into surrounding tissues. Yet, not all pathways point toward late diagnosis. Increasing awareness, surveillance for high-risk groups, and improvements in endoscopic detection have carved out opportunities for earlier intervention. Understanding the terrain—what type of cancer, where it is, and how it behaves—provides the map for decisions that follow.

Risk Factors and Prevention: From Lifestyle to Environmental Exposures

Risk for esophageal cancer emerges from a tapestry of influences—some you can change, others you cannot. Tobacco and heavy alcohol use are classic risk factors for squamous cell carcinoma, and together they can have a multiplying effect. Long-standing gastroesophageal reflux and obesity are closely tied to adenocarcinoma, especially when reflux leads to Barrett’s esophagus. Diets low in fruits and vegetables, certain pickled or preserved foods, and chronic exposure to very hot beverages have been associated with higher risk in some populations. Medical conditions such as achalasia, prior caustic injury, or previous chest radiation can also raise risk.

Not all risk is destiny. Several prevention strategies are supported by clinical experience and population studies, and many dovetail with broader wellness goals. While individual actions don’t guarantee prevention, they can lower the odds and improve overall health in the process:

– Avoid tobacco in all forms; cessation support, counseling, and pharmacologic aids can make a meaningful difference.

– If you drink alcohol, consider moderating intake; heavier use carries higher risk, particularly for squamous cancers.

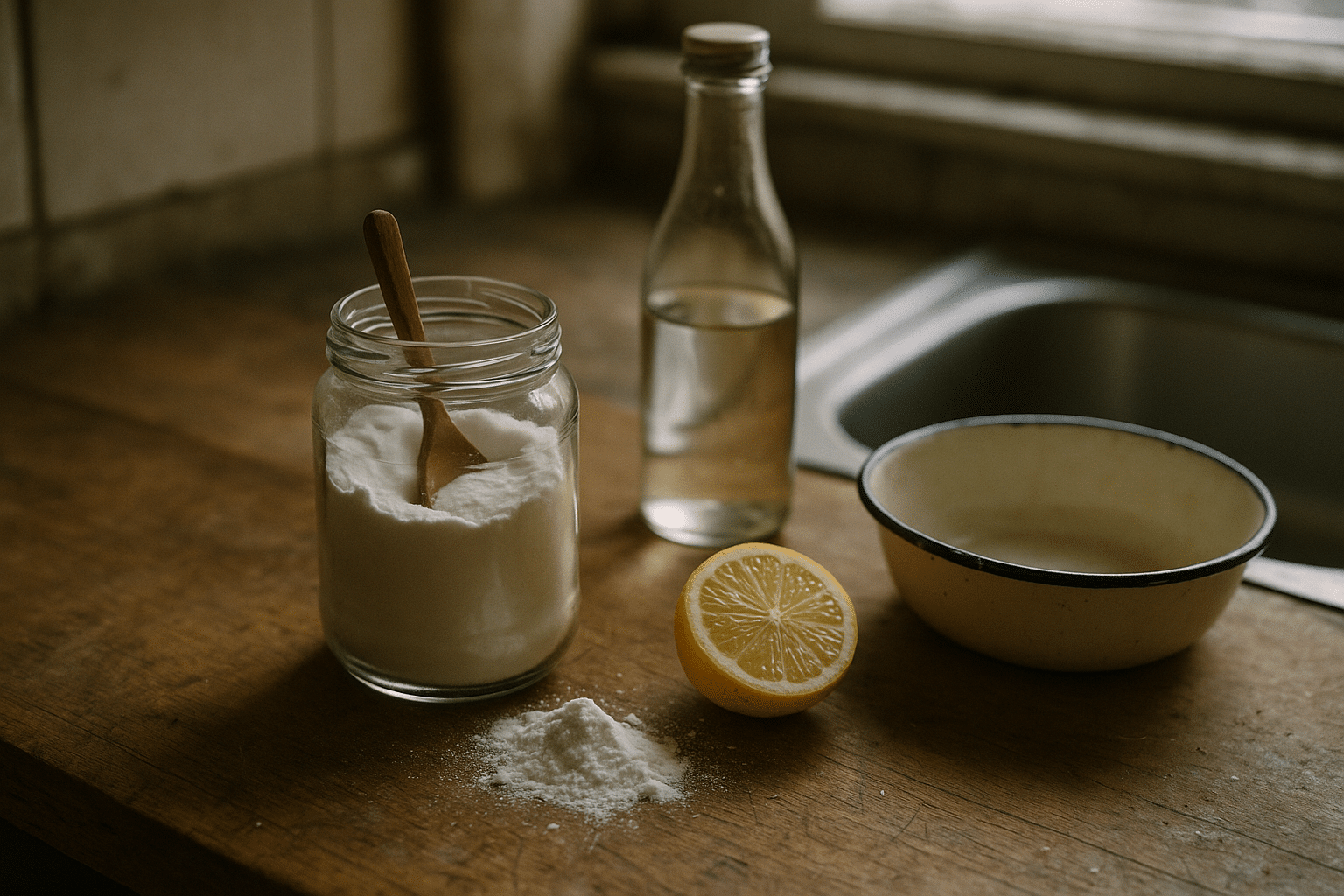

– Address reflux symptoms early; weight management, meal timing, and sleeping with the head of the bed elevated may help, alongside clinician-guided medications when indicated.

– Aim for a varied, plant-forward eating pattern rich in fiber, colorful vegetables, fruits, and whole grains.

– Be cautious with very hot beverages; letting drinks cool slightly can reduce thermal injury to the lining.

– Discuss surveillance if you have known Barrett’s esophagus or long-standing achalasia; periodic endoscopy can detect precancerous changes.

Community and environmental factors matter, too. Access to fresh foods, safe water, and timely medical care influences risk and outcomes. In regions with high incidence of squamous cell carcinoma, public health efforts that reduce tobacco and alcohol use, improve nutrition, and address occupational exposures have shown value. For individuals with strong family histories or rare syndromes that affect DNA repair, tailored counseling can clarify personal risk and screening options.

Prevention works best as a series of small, sustainable steps rather than sudden, sweeping changes. Think of it as tending a garden: consistent attention to soil, water, and light helps resilience take root. Even when risk cannot be erased, shaping the environment of the esophagus—through diet, lifestyle, and proactive care—can shift the trajectory toward earlier detection and stronger treatment options.

Signs, Symptoms, and Diagnosis: From Subtle Hints to Definitive Tests

Early esophageal cancer can be quiet, but the body often whispers before it shouts. One of the most common early clues is dysphagia—difficulty swallowing—that typically begins with solids and can progress to liquids. People might unconsciously adjust by eating slower, taking smaller bites, or choosing softer foods. Other symptoms include unintentional weight loss, chest or back discomfort, heartburn that changes in pattern, hoarseness, persistent cough, or regurgitation. Less commonly, bleeding can show up as anemia or dark stools. None of these signs confirm cancer on their own, but a pattern that worsens warrants prompt assessment.

Evaluation begins with a careful clinical history and physical examination, followed by tests that visualize the esophagus and assess nearby structures. Endoscopy is the key tool: a clinician passes a flexible scope to directly inspect the lining, biopsy suspicious areas, and sometimes remove early lesions. Imaging studies help define the extent of disease. Each test has a particular role, and they often work best together:

– Endoscopy with biopsy: provides tissue diagnosis, can detect subtle lesions, and allows therapeutic procedures for very early cancers.

– Endoscopic ultrasound: helps determine how deeply a tumor invades the wall and whether nearby lymph nodes are involved.

– Contrast swallow (barium): outlines strictures and can identify motility disorders; useful when endoscopy is not immediately feasible.

– Cross-sectional imaging (CT) and metabolic imaging (PET): assess spread to lymph nodes or distant organs and guide staging.

– Bronchoscopy or additional airway evaluation: considered for tumors near the upper esophagus where the airway may be affected.

Diagnosis is more than naming a disease; it is about understanding its stage and biology. Pathologists determine whether a tumor is squamous or gland-forming and look for features such as grade and margins. In many centers, additional testing examines biomarkers that can inform therapy selection in advanced disease. For those with Barrett’s esophagus, surveillance protocols aim to detect dysplasia—precancerous change—at a stage when endoscopic therapy can be curative. The sooner a clear picture emerges, the more choices patients typically have.

It can feel daunting to move through these steps, but there is a rhythm to the process. First, identify the problem; second, obtain tissue; third, stage the disease; and finally, plan treatment. Along the way, clinicians balance accuracy with safety and comfort, tailoring tests to each person’s situation. Even in uncertainty, the diagnostic path functions like a well-marked trail: each signpost narrows the possibilities and points to the next right step.

Staging and Treatment Options: Surgery, Systemic Therapy, and Radiation

Staging sets the strategy. Using tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) criteria, clinicians classify how deeply the tumor invades the esophageal wall, whether lymph nodes are involved, and whether the cancer has spread to distant organs. Early disease limited to the mucosa (T1a) can sometimes be treated endoscopically by removing the lesion and ablating surrounding dysplasia. When the tumor invades deeper layers (T1b and beyond), surgical resection becomes a central option for cure in suitable candidates. For locally advanced cases, combinations of chemotherapy and radiation before surgery often improve control.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach, and treatment planning usually happens in a multidisciplinary setting that brings together surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, pathologists, radiologists, and supportive care specialists. The goals of therapy shape the plan:

– Curative intent: for resectable tumors, with appropriate combinations of surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and endoscopic therapy for early lesions.

– Disease control: for locally advanced or medically inoperable cases, using chemoradiation or systemic therapy to shrink or stabilize disease.

– Symptom relief: for advanced or metastatic disease, focusing on swallowing, pain, nutrition, and overall quality of life.

Systemic therapy includes chemotherapy backbones that target rapidly dividing cells; in selected cases, targeted agents are used when specific biomarkers are present (for example, overexpression of certain growth factor receptors). Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors may be considered for some advanced tumors based on tumor features. Radiation can be delivered alone or with chemotherapy, and it can also be used to palliate symptoms like painful swallowing. Endoscopic stenting to prop open the esophagus can restore nutrition and comfort when surgery is not an option.

Choosing among these paths depends on tumor type (squamous vs. adenocarcinoma), location, stage, overall health, and personal preferences. Surgical techniques vary from minimally invasive approaches to more extensive operations, each with distinct recovery timelines and risks. Chemotherapy regimens and radiation dosing are tailored to minimize toxicity while maintaining effectiveness, and newer strategies continue to evolve in clinical trials. Shared decision-making is crucial; understanding potential benefits, side effects, and what life might look like during and after treatment helps align care with individual priorities.

Treatment is a journey with milestones, not a single leap. Even when cure is the aim, building in supportive measures—from swallowing therapy to symptom management—can make the road more navigable. And when the focus is comfort and time, thoughtful palliative care can turn a narrow path into one with more room for breath, taste, and meaningful moments.

Living With and Beyond Esophageal Cancer: Nutrition, Side Effects, and Supportive Care

Life during and after esophageal cancer treatment is shaped by how well people can eat, drink, and maintain energy. Swallowing rehabilitation, nutrition counseling, and individualized meal planning are practical anchors. Small, frequent meals, careful chewing, and upright posture after eating can ease passage through a narrowed or healing esophagus. Energy-dense foods and high-protein options help preserve weight, and for those who cannot maintain adequate intake, temporary feeding tubes can support recovery. Hydration deserves its own plan, especially during chemotherapy or radiation, when nausea or soreness can discourage fluid intake.

Side effects vary by treatment and are highly individual, but patterns are familiar. Radiation can cause inflammation of the esophagus, leading to pain with swallowing; chemotherapy can contribute to fatigue, taste changes, or neuropathy; surgery may alter anatomy and cause reflux or dumping symptoms. Practical strategies can soften the impact:

– Use texture modification (soups, smoothies, soft solids) during flares of pain or narrowing.

– Keep a symptom diary to spot triggers and track what helps; bring it to clinic visits.

– Practice oral care routines to reduce mouth soreness and risk of infection.

– Work with a dietitian on calorie and protein targets, and consider nutrient supplementation if deficiencies develop.

– Ask about medications to manage reflux, nausea, pain, or bowel changes, and about swallowing therapy for stricture or coordination issues.

Emotional and social health matter as much as calories and scans. The experience can feel isolating, especially when eating—a social ritual—becomes challenging. Early integration of palliative care focuses on symptom relief and aligns treatment with personal goals; it complements, rather than replaces, disease-directed therapy. Rehabilitation services can improve strength and endurance, while counseling and peer support normalize fear and uncertainty. Caregivers, too, benefit from concrete guidance on meal preparation, appointment logistics, and respite options.

After treatment, surveillance follows a schedule tailored to stage and therapy, with periodic exams and imaging or endoscopy when indicated. Long-term considerations include managing reflux, preventing strictures, monitoring weight and micronutrient status, and paying attention to bone and heart health when treatments may have lingering effects. Many people gradually rebuild routines—returning to work, rediscovering flavors, and adapting recipes to new realities. Progress often arrives quietly, like a door opening a little wider each week. With attentive follow-up and a toolkit of practical supports, living well remains a steady, attainable aim.

Conclusion

Esophageal cancer reshapes daily life in ways both obvious and subtle, but knowledge restores agency. By understanding risk factors, recognizing symptoms early, and engaging in shared decisions about testing and treatment, individuals and families can better navigate a difficult diagnosis. Whether the goal is cure, control, or comfort, attention to nutrition, symptom relief, and emotional well-being strengthens every plan. Keep asking questions, keep notes, and keep your circle of care close—these are the habits that turn information into momentum.