Container Houses: A Practical, In-Depth Guide to Design, Costs, and Building Requirements

Outline

– Understanding container houses: benefits, drawbacks, and common sizes

– Design and space planning: structure, insulation, and layouts

– Costs and budgeting: line items, examples, and savings opportunities

– Permits and building requirements: codes, foundations, and process

– Conclusion and next steps: sustainability, maintenance, and decision-making

Introduction

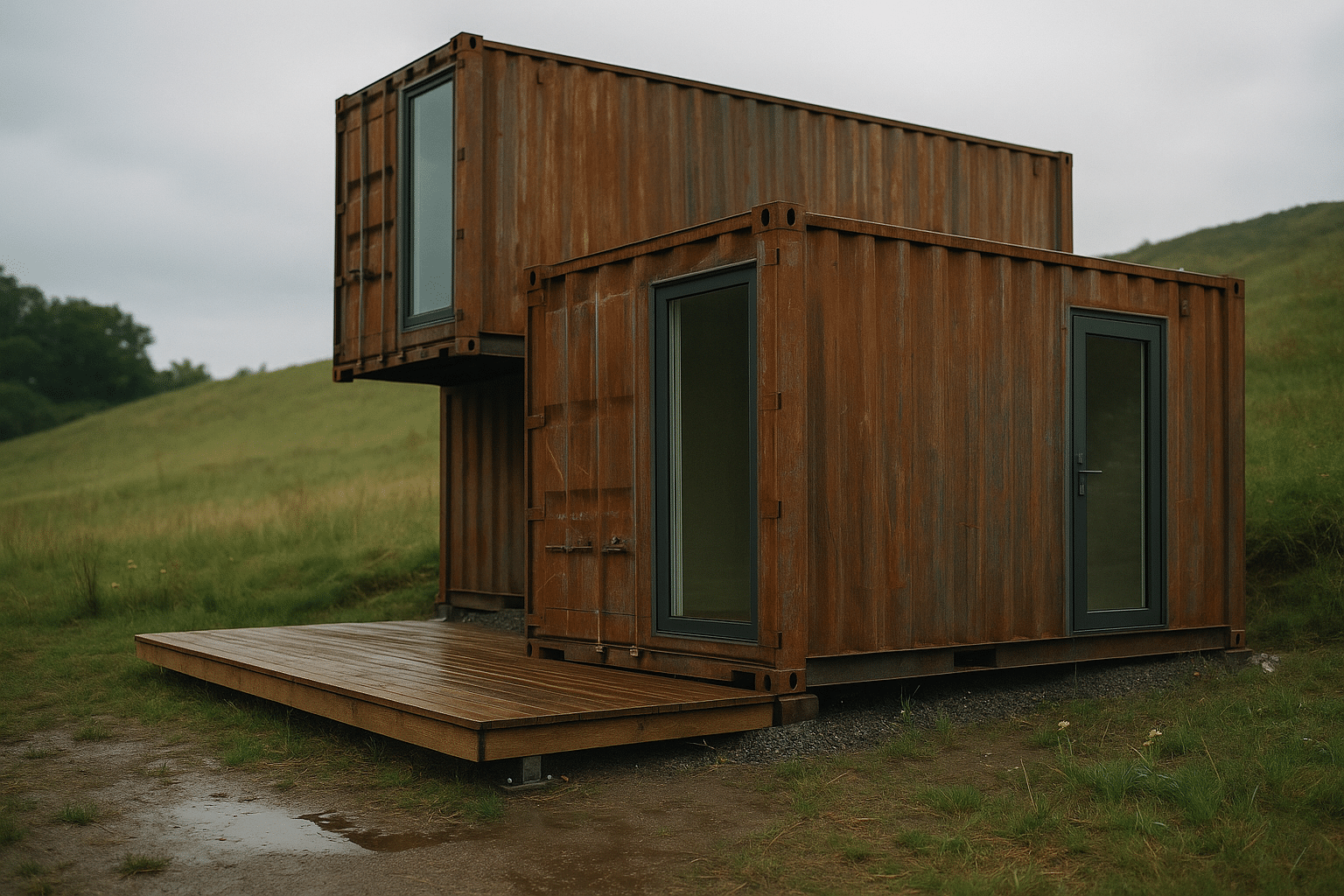

Container houses turn surplus cargo boxes into livable architecture, pairing speed and durability with compact, modular footprints. For people balancing budget, schedule, and flexibility, the approach offers a compelling alternative to conventional site-built construction. This guide walks you through fundamentals, from design choices and cost planning to permits and long-term care, so you can judge whether a container home aligns with your goals.

Basics: What Container Houses Are—and What They’re Not

At their core, container houses are homes built from standardized steel cargo boxes originally engineered for ocean, rail, and truck transport. The rigid corner posts, corrugated steel walls, and steel cross members are designed to stack heavy loads and resist racking in tough conditions. The two most common sizes are 20-foot (about 160 square feet of floor area) and 40-foot (about 320 square feet). “High-cube” variants add roughly a foot of interior height (to about 9 feet 6 inches exterior), which provides more headroom for insulation, ducting, and comfortable interiors.

Why they matter: containers offer dimensional predictability, structural robustness, and modularity that can compress timelines and reduce some framing tasks. They can be transported on standard trailers and set with a crane or telehandler in hours, accelerating dry-in if the design is well coordinated. However, a container alone is not a finished house. It needs insulation, windows, doors, vapor and air control layers, electrical and plumbing runs, interior finishes, and a foundation that matches soil and climate requirements.

Common advantages include durability, the potential reuse of industrial materials, and compact footprints suitable for infill sites. Yet there are trade-offs. Cutting large openings for glazing and doors removes structural steel, requiring engineered reinforcement. Bare steel is a strong thermal conductor, which makes thermal bridging and condensation real risks if not addressed with detailing and insulation. And while the box arrives fast, interior fit-out, code compliance, and site work often take as long as conventional building methods.

Myths to avoid:

– “It’s automatically cheaper.” In many regions, total build cost per square foot can be similar to small high-quality wood-frame homes once you include transport, cranes, structural welding, insulation, and finishes.

– “It’s plug-and-play.” Containers are a shell; turning them into a code-compliant dwelling requires the same level of design and permitting as other small homes.

– “Any container will do.” Previous cargo use, floor treatments, denting, and corrosion vary widely; selection and remediation matter for health and durability.

Bottom line: a container house is a legitimate building method with clear strengths—modularity and strength—and clear responsibilities—engineering, moisture control, and code compliance. Success depends on treating the container as a structural module within a rigorously detailed building system, not as a finished product.

Design and Space Planning: Layouts, Structure, and Comfort

Good outcomes start with the plan. Begin by mapping daily routines—where you cook, work, store gear, and unwind—and prioritize the sequence of spaces. A single 40-foot container supports a compact studio with a galley kitchen and bathroom, while two 40-foot units can form a 640-square-foot home with one or two bedrooms. Arranging containers in an L-shape can create a sheltered courtyard and bring daylight to more walls; stacking high-cube units can add a mezzanine or loft while staying within many height limits.

Structure comes first. Cutting a big window or a 12-foot sliding opening removes corrugated steel that contributes to lateral stability. A typical solution is to frame the opening with welded steel box sections or channels that transfer loads to the corner posts. Where multiple containers are joined, stitch plates and perimeter beams can unite the modules and minimize differential movement. Work with a structural professional who understands wind and seismic loads in your region; uplift connectors, tie-downs, and diaphragm action are as critical as the cuts themselves.

Comfort hinges on the building envelope. Steel’s high conductivity makes condensation control essential. Strategies include:

– Continuous exterior insulation to interrupt thermal bridges at corrugations (rigid mineral wool or foam boards behind a ventilated rain screen).

– Closed-cell spray foam applied to interior steel when exterior insulation is impractical; aim for a continuous air and vapor control layer with sealed seams.

– Careful detailing at floor and roof edges, where steel ribs and framing can bypass insulation.

Typical R-values vary by product and thickness; for example, closed-cell spray foam often delivers roughly R-6 to R-7 per inch, while mineral wool boards are around R-4 per inch. Choose assemblies that comply with your local energy code and climate zone. Ventilated rain screens help dry trapped moisture and protect coatings. On roofs, consider a slight overbuild: add tapered insulation for drainage, a continuous membrane, and a ventilated cap or canopy to limit solar heat gain.

Systems integration requires forethought in a tight shell. Run plumbing along interior service walls to avoid freezing at the steel skin. Use low-profile mini-ducted heat pumps or wall-mounted heads where appropriate, and plan condensate routing. Fresh air is non-negotiable in tight homes: a small heat-recovery ventilator can maintain healthy indoor air while limiting energy penalties. For acoustics, resilient channels, dense insulation, and layered gypsum assemblies tame reverberation and rain noise on the roof.

Finally, think daylight and privacy together. Tall, narrow windows between corrugations preserve more structure and add rhythm; clerestory glazing can wash ceilings with light while protecting privacy. Pocket doors, built-in storage, and a continuous floor finish can make compact plans live larger. Design restraint—edited materials and a coherent color palette—goes a long way in a small footprint.

Costs and Budgeting: Real Numbers, Hidden Line Items, and Trade-Offs

Costs vary widely by region, labor market, and scope, but certain patterns repeat. A used 40-foot high-cube container often trades in the rough range of a few thousand to the low five figures, while “one-trip” units land higher. Delivery within a region may cost a few hundred to a few thousand depending on distance, site access, and whether a tilt-bed or crane is needed. Steel modifications—door and window cuts, welded frames, and stitch plates—can be a substantial portion of the budget, especially if site welding and inspections are required.

As a planning baseline, many owner-builders report all-in costs for well-finished container homes in the vicinity of roughly 150 to 350 per square foot, with simple, utility-focused builds landing lower and architecturally ambitious projects higher. That range typically includes foundation, container(s), structural reinforcement, insulation, doors and windows, mechanical systems, interior finishes, labor, and soft costs. In high-cost urban areas, totals can exceed that range due to labor, permitting complexity, and site constraints.

Expect these drivers to move your budget:

– Site work: grading, driveway, utility trenching, and septic or sewer connection can add 10–25% or more.

– Foundation: helical piles, piers, or a slab can range from a few thousand for small footprints to tens of thousands for complex soils.

– Craning and staging: tight sites that require larger cranes or road closures carry premium fees.

– Envelope quality: exterior continuous insulation, rain screens, and high-performance windows add up front, but reduce operating costs and moisture risks.

– Soft costs: design, engineering, permits, surveys, and energy modeling typically total 8–20% of construction cost.

Consider a simple example: two 40-foot high-cube containers joined side by side to create about 640 square feet. Hypothetical budget bands might look like this in many markets:

– Containers and delivery: 8,000–24,000

– Structural modifications and welding: 10,000–30,000

– Foundation and anchoring: 6,000–20,000

– Insulation, windows, doors, and weather barrier: 18,000–45,000

– Mechanical, electrical, plumbing: 15,000–35,000

– Interior finishes and cabinetry: 12,000–35,000

– Soft costs and contingencies: 15,000–40,000

Those ranges are illustrative, not a quote. The lesson: container projects concentrate costs in steel work and envelope performance rather than traditional framing. To manage expenses, prioritize a simple structural concept (fewer, well-placed openings), standardized window sizes, and an exterior insulation system that balances performance with labor. Bid craning early, schedule inspections efficiently, and keep a 10–15% contingency for surprises like rock excavation or weather delays.

Permits, Codes, and Building Requirements: From Zoning to Final Inspection

Container houses must meet the same legal baseline as conventional homes. Start with zoning: confirm that a dwelling is allowed on your parcel, check setbacks, height limits, parking requirements, and any aesthetic guidelines. Some jurisdictions define “modular” or “industrialized” buildings differently; ask your local building department how they classify container-based construction. If your home will be on wheels or temporarily sited, different rules may apply, but permanent foundations typically trigger residential building code compliance.

The building code covers structure, energy, fire safety, plumbing, electrical, and mechanical systems. Structural review will focus on wind and seismic forces, connections between containers, and any reinforcement where walls are cut. Energy compliance requires meeting prescriptive or performance targets for insulation, windows, air sealing, and mechanical efficiency. In fire safety reviews, expect scrutiny of egress windows (minimum opening sizes), bedroom smoke alarms, carbon monoxide alarms, and ignition-resistant exterior materials in wildfire-prone areas.

Foundations must match soil and climate. Options include:

– Concrete piers or strip footings with anchoring plates to the container’s corner castings.

– Helical piles for minimal excavation and adaptable installations on sloped or sensitive sites.

– A full slab with embedded connectors, which can simplify utilities and control pests in some climates.

Approvals move faster when drawings are complete and coordinated. A strong submittal typically includes:

– Architectural plans and elevations showing window and door sizes and locations.

– Structural details for cutouts, reinforcement, tie-downs, and inter-container connections.

– Foundation plan and geotechnical recommendations or presumptive soil bearing values.

– Energy documentation (load calculations, insulation values, and ventilation strategy).

– Site plan with grading, drainage, utilities, and access for emergency services.

Inspections occur at predictable milestones: foundation, underground plumbing and electrical, framing/structural, rough-in mechanical, insulation and air barrier, and final. If you prefabricate off site, the jurisdiction may require factory inspections or third-party certification; coordinate early to avoid rework. Pay attention to corrosion protection: any new welds and cut edges should be primed and coated per manufacturer specifications for the coating used, and exterior penetrations should be sealed with compatible flashings. Lastly, document container provenance and condition (serial number, prior cargo category, and remediation if floors were treated) to answer health and safety questions proactively.

Conclusion and Next Steps: Sustainability, Longevity, and Owner Priorities

If you’re drawn to container housing for its mix of resilience and speed, frame your decision around performance and lifecycle—not marketing images. Reuse can be meaningful, but context matters. A 40-foot container typically weighs several tons of steel, and the embodied carbon of primary steel is significant; repurposing a unit that would otherwise sit idle reduces demand for new materials, but using a nearly new “one-trip” unit for architecture may reduce that benefit. Durable envelopes, right-sized mechanical systems, and thoughtful detailing will do more for long-term impact than any single material choice.

Longevity depends on water management and maintenance. Provide generous overhangs or a capping roof to limit solar gain and rain exposure. Elevate containers off the ground, keep vegetation away from the steel skin, and slope grades so water leaves quickly. Inspect coatings annually; address scratches, worn edges, and weld seams early to prevent corrosion from spreading. On the interior, keep humidity in check with balanced ventilation and spot extraction at kitchens and baths; condensation control is a daily practice, not a one-time install.

For many owners, the path forward is clearest when broken into steps:

– Define your program and constraints: household size, climate, budget, and timeline.

– Choose a structural concept with minimal large cutouts; let window rhythm follow corrugation spacing when possible.

– Decide where insulation lives (exterior, interior, or hybrid) and model the assembly for condensation risk.

– Engage a design professional and a structural engineer with container experience.

– Verify zoning, then schedule a pre-application meeting with your building department to align on submittal requirements.

Finally, pressure-test your numbers. Price delivery, craning, and foundations based on your actual site. Get at least two bids for steel modifications and set a contingency. If your totals align with your goals and the design fits your climate and lifestyle, proceed with confidence; if not, you’ve built knowledge that transfers directly to other compact, energy-efficient housing types. A container house is not a shortcut to a dream home, but it can be a smart, durable, and expressive route when planned with rigor and a clear-eyed budget.